On 26 November a History of Cartography work group organized a special day around the Atlas of the Netherlands for an interested general audience. The last presentation of the day was entitled 'Damaged mapped' of Jean-Marieke Poot en Judith Geerts. This is a short summary of their findings.

Principles

- the unique physical shape of the Atlas should not be changed (keep all maps in their binders, including Volume 9);

- the history of the Atlas (with all the traces time has left), should stay visible. No cosmetic cover-ups;

- Primarily, the aim is scientifically justified conservation;

- because the entire Atlas will be digitized,in the future it will hardly ever be necessary to use the historical object itself.

Damage

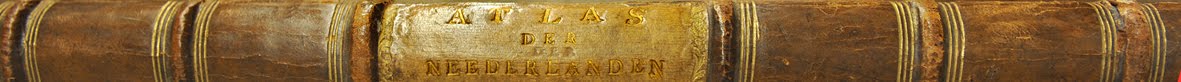

Damage to the leather binders

- damage at the corners;

- degradation of the leather;

- surface dirt.

Damage to the maps

- chemical damage (foxing, copper corrosion, ink corrosion);

- climate damage (damp stains, fungus, 'wavy pages');

- surface dirt (dust, stains from dirty fingers. Dirt is hygroscopic and attracts moisture, which is good for fungus)

- mechanical damage (damage by use, false folds, tears, maps getting loose from the binder);

-

undo 'earlier repairs'.

Recommendations

Volume 1, 2 en 3 are in fairly to good shape. Volume 9 is not in a very good shape. The cause seems to be the frequency of use. The damage to the binders is not that big. Most of the damage is to the paper.

The binder

- reinforce and restore where necessary

The maps

- repair tears where necessary;

- dry clean dirt;

- where possible, flatten the folds that cause unnecessary tension;

- where possible, repair wrongly executed repairs of the past;

- (only) while working on Volume 9, maps can be taken out of the binder, and placed back after restoration;

- a clear and very restrictive access policy of the Atlas after restoration.

Poot and Geerts felt there should be clear rules as to who can see what and under what circumstances and terms. The rules for volume 1, 2 and 3 could be less strict than, for example, volume 9. And less strict for maps that have not been folded, or folded only once, than for the more complexly folded maps.

This - and more, I'm sure - will later be discussed at a meeting of experts. But this afternoon, all nine volumes were on view on a large oval table for all the white-haired to see. Volume 9 put safely in the middle.